Leviticus and the Liturgy in Your Pocket

If you’re like me, your phone is too often the first light you see in the morning.

Before prayer. Before coffee. Before you’ve really arrived in your own day.

You reach, almost without choosing, to check the news, your calendar, your inbox. And within seconds you’re not simply “getting information.” You’re being formed. Your digital discipleship is in full swing. Your attention is captured, your body is tuned to urgency, your imagination filled with competing demands. You may still be lying in bed, but you are already standing before an altar.

That may sound dramatic. But Leviticus gives us language for what’s happening.

Most modern readers approach Leviticus expecting “religious stuff”—sacrifices, priests, strange rules about bodies and blood and food. I’ve been teaching Leviticus for a long time now and more recently had to do a deep dive for a book I’m working on. I’m convinced that Leviticus isn’t interested in “religion” as a compartment of live. It’s interested in formation of the whole person for all of life. It assumes something deeply realistic about human beings: we become what we repeatedly do. Our loves are trained through rhythms, routines, and embodied practices. Long before anyone talked about “habit loops” or the “attention economy,” Leviticus offered a divinely scripted way of life meant to shape a people in the presence of God for the sake of the world.

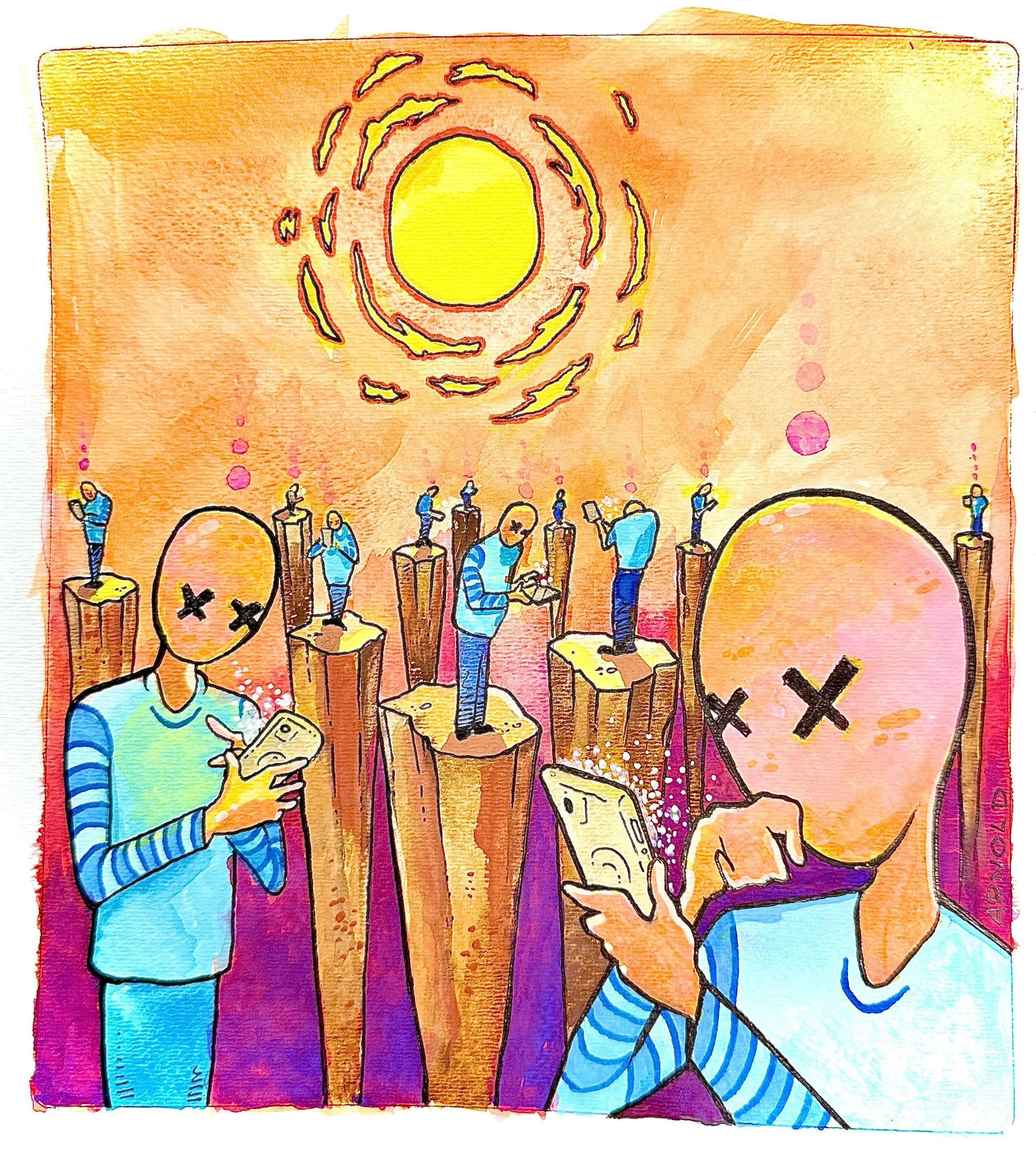

And here’s the uncomfortable implication: if Leviticus is right, then our digital habits are not neutral. Our cultural moment has its own liturgies, bright, frictionless, always available. They do not ask for incense or sacrifice, but for our attention, for our devotion. These practices are carefully designed and relentlessly optimized by people and systems whose goals are not our holiness, our peace, or even our happiness, but our engagement, our data, and our time. Algorithms are engineered to keep us scrolling and reacting; notifications are calibrated to interrupt; feeds are shaped to provoke desire, outrage, comparison, and fear. They promise connection, affirmation, and control, yet often leave us lonely, anxious, distracted, and fragmented. And because these rituals live in our pockets, they follow us everywhere, dissolving boundaries between work and rest, prayer and news, presence and performance; daily liturgies scripted by forces that do not know us and do not love us.

Leviticus pushes back by training three things our devices quietly erode: boundaries, attention, and return.

First, Leviticus teaches that boundaries protect what matters. The tabernacle is full of thresholds, of courts, curtains, restricted access, because presence is powerful. Not everything belongs everywhere. Our phones, by contrast, are boundary-collapsers. A phone-free table, bedroom, or hour is an act of wisdom not legalism. It says: presence matters here.

Second, Leviticus teaches that attention is trained through practice. Daily rhythms, weekly Sabbaths, and seasonal feasts shaped Israel to see time as gift, the body as gift, and memory of God’s work and cultivation of God’s presence as central. Our devices powerfully train us too but often toward haste, comparison, and constant stimulation. The question is not whether we are being formed, but how, by whom, and to what end.

Finally, Leviticus teaches that drifting is normal and return must be practiced. Ordinary Israelites moved in and out of ritual impurity through everyday life. The goal was not perfection but attentiveness and restoration. That maps uncomfortably well onto our digital lives. We scroll when we are tired, bored, anxious, or lonely. The problem is not drifting; it’s never returning.

A Leviticus-shaped response doesn’t begin with grand vows, but with intentional acts of return. Sometimes theses are small and repeatable, and sometimes more radical when required. For some, this may mean a phone-free beginning to the day, a protected Sabbath window, or a physical place where the phone rests when presence is required. For others, especially when habits have become compulsive or corrosive, wisdom may call for stronger boundaries: deleting apps, limiting access, or even adopting a “dumb phone.” Crucially, in Leviticus these practices are never merely private strategies but communal commitments, undertaken within a people who share responsibility for one another’s faith and life. Recovery of attention, like holiness itself, is sustained by shared rhythms, mutual accountability, and a community willing to name and practice a different way of life together.

This emphasis on practice, however, is only one strand of Leviticus’s larger wisdom. Leviticus is not merely a manual about ritual and habit; it offers a comprehensive vision of life with God—one that takes human limits seriously, builds rhythms of repair rather than perfection, binds worship to justice, and insists that holiness is communal, embodied, and costly. The same book that teaches Israel how repeated practices shape desire also teaches them how to give generously from their labor, how to eat attentively within creation’s limits and in celebration with the whole community, how to honor vulnerable bodies, and how to refuse worship that is detached from love of neighbor. The practices that challenge our digital habits are therefore part of a wider invitation: to become a people shaped for life with God over the long haul, whose healed attention and shared life bear quiet witness in a distracted and fragmented world.

Tomorrow morning, before you touch your phone, put your feet on the floor and take one deep breath. Pray one sentence: “Lord, gather me—my scattered thoughts, my divided attention, my whole self.” Begin the day not with the liturgy in your pocket, but with the God who meets you in the ordinary.

By: David Beldman

The artwork featured in this piece was created by Arnold Guerrero and explores themes of attention, captivity, and the spiritual cost of distraction.